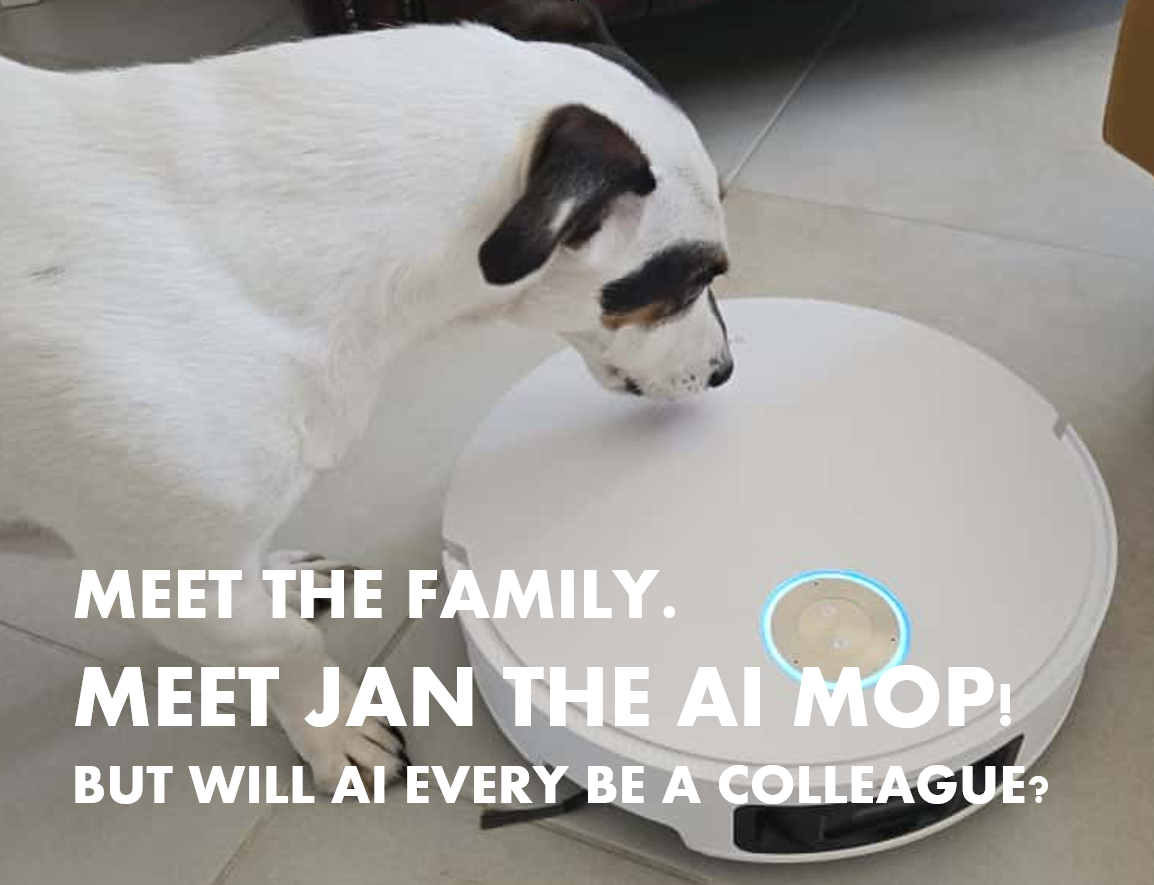

Jan the AI Mop – why I’ll let a robot be family, but never a colleague (just yet anyway)

I said it on before and on stage, and I’ll say it again: AI is not your friend, it’s not your mate and it’s not your colleague. But let me tell you about Jan the AI Mop – the one exception to my hard line. Jan is welcome in my kitchen, on the floor tiles, and under my feet. Just don’t expect Jan to take my 1:1s.

This is a tongue-in-cheek look at what it feels like to treat automation like family, while still being ruthlessly clear about where humans belong. Spoiler: I apologise to a mop. You might too.

Jan arrived as a tidy little box a few months ago to the Fox Household, with wheels and a weirdly optimistic voice. She does two things flawlessly: vacuum and mop. She navigates our living room like she owns it, slips under the sofa without complaint, and returns to her base when the battery’s low. No drama. No opinions. No passive-aggressive emails.

One afternoon last week I popped downstairs for a cuppa and literally bumped into Jan. My immediate reaction – out loud – was: “Sorry, Jan.” And I paused. Why did I apologise to a machine? Because Jan occupies the same physical space as Scrappy, our dog. But here’s the difference: Scrappy follows me around without any task other than his fixation with eating whatever I drop crumps in the kitchen – and he doesn’t always do what he’s told. Jan, on the other hand, just gets on with it.

If that sounds ridiculous, that’s because it is. But it’s also human. We anthropomorphise. We give names. We create relationships – even with things we know are just code and motors.

“We want AI to do our work – not our jobs”

This is the line I’ve been pushing: automation should take the repetitive, the low-value, the tedious – the vacuuming, the data-entry, the tedious report formatting. Let AI mop the floors of our working lives so humans can do the messy, uncertain, creative, moral work that actually moves a business forward.

Jan the Mop embodies that idea perfectly. She doesn’t reduce anyone’s dignity by taking over an unpleasant task. If anything, she frees up one more 15-minute slot in my day for a meaningful conversation, a proper decision, or a walk with Scrappy.

It’s tempting to conflate Jan with the notion of all AI – but there’s a key difference.

-

Jan is a single-purpose system. Her world is simple: map the room, avoid the dog, mop. When she does her job she does it reliably.

-

The kind of AI that worries people – large language models, multi-agent systems – are trained on broad, messy datasets. They generate behaviour that looks human, but it’s stitched together from millions of data points that have nothing to do with your context, culture, or values.

-

Jan does what you tell her to do. Generalist AI often seems to do what you think you told it to do – and sometimes it changes its mind halfway through.

So Jan doesn’t lie, hallucinate, misinterpret your contractual obligations, or propose half-baked corporate strategies. She cleans. She is gloriously boring.

The uncanny valley of usefulness

The problem with taking general AI seriously as a “colleague” is twofold:

-

Unpredictability. A mop doesn’t rewrite the strategy deck because it read an article. A generative model might. That unpredictability creates risk – reputational, legal, operational.

-

False familiarity. When a tool talks like a human, we start treating it like one. We outsource judgement. We defer. We forget that the ‘voice’ isn’t wisdom – it’s pattern matching.

That’s why the mantra matters: give AI tasks that are bounded, measurable, and auditable. Let it sweep up the crumbs; don’t let it decide who to hire.

Part of the reason Jan feels safe is her limitations – they are obvious. With general AI, limitations are hidden. The model looks convincing until it isn’t. It’ll invent references, change tone randomly, or apply an entirely different cultural assumption to a problem. That’s the point where you can’t have it sitting on the executive team.

AI should be used where its failure modes are visible and manageable. Jan’s mistakes are obvious: she misses a patch of tiles, she gets stuck under the sofa. You can see, fix, and learn. When a model fabricates a statutory requirement or rewrites a contract clause – the stakes are higher, and the failures are stealthy.

Here’s the honest bit: the work that matters – leadership, judgement, empathy, moral choice, negotiation – can’t be handed to Jan or any other mop. Those things require context, history, courage and sometimes awkwardness. They need us.

Let the machines be excellent at the mechanical. Let them be reliable, single-purpose servants. And let us be the ones who decide what’s important, who weigh trade-offs, and who own the outcomes.

A small experiment in humility

Try this little experiment at home or at work: list three tasks you hate doing that don’t require judgement. If one of them can be automated, let it go. Reclaim that time. Use it for a conversation, a sprint, a walk, or a poorly timed cuppa.

If you find yourself apologising to the tech – good. It’s a sign you’ve already made room for it in your life. But don’t confuse warmth with authority. You’re still the boss.

Jan the AI Mop is part of the family. She’s reliable, modest and slightly over-friendly about corner cleaning. But Jan’s companionship doesn’t change the rules. AI’s place is to extend our capacity, not to replace our conscience or our teams.

We want AI to do our work – the repetitive, the boring, the dangerous. We don’t want AI to do our jobs. Names, feelings and reluctant apologies to vacuum robots are fine. Conferring responsibility on an algorithm – that’s not fine.

So yes – apologise to Jan if you must. Then fill the extra time Jan gives you with something only a human could do (like cuddles and walks with Scrappy).